Back to School: How a School Reunion Changed the Narrative

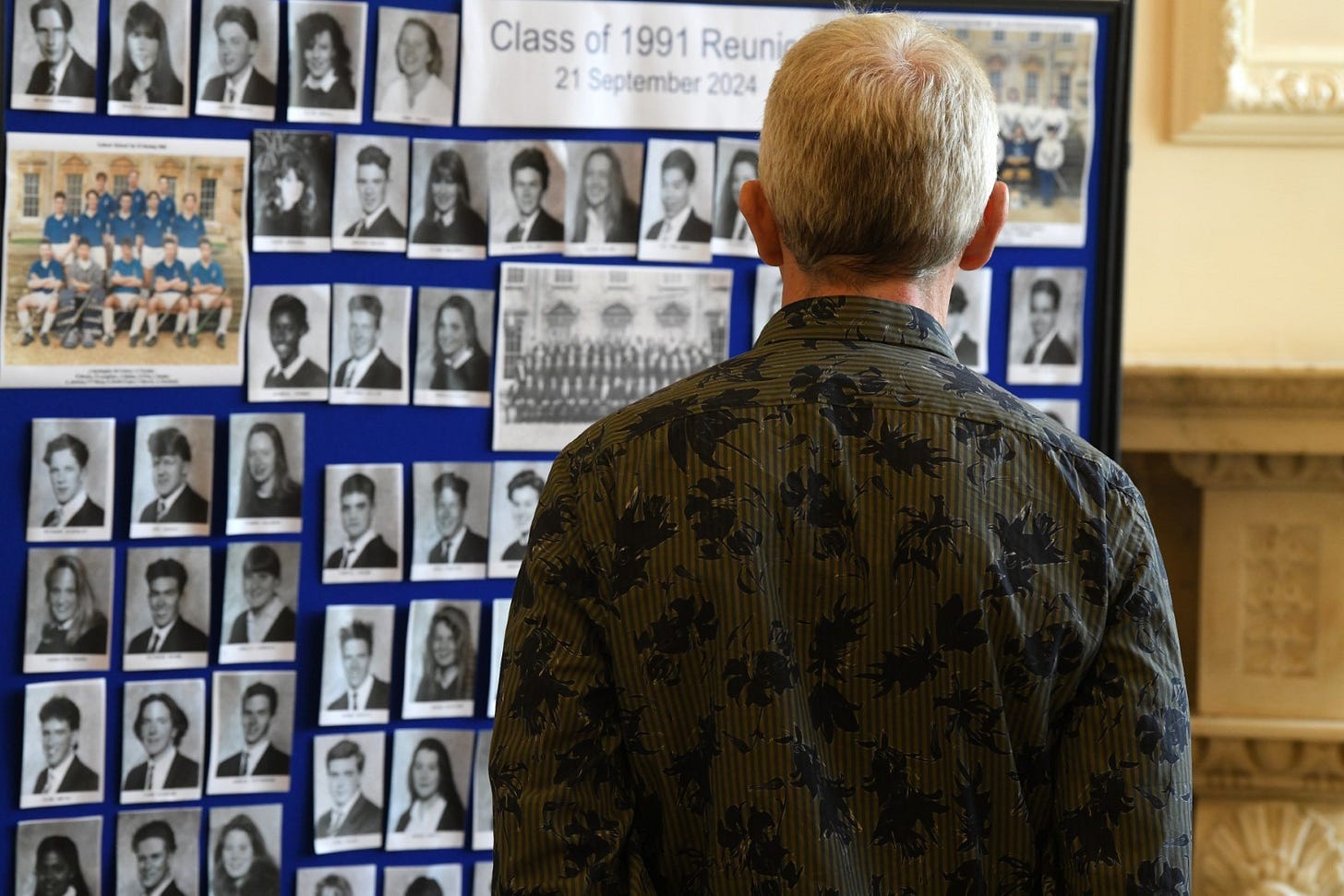

Past failures, triumphs, and unexpected connections as the Class of '91 reconvene

Hanging in one corner of the Old Hall at Culford School where the Class of 91 convened for their reunion is a portrait of a former headmaster. Derek Robson (pictured above top right) is seen leaning back with his legs crossed, thick black hair, and a nonchalant look on his face. A distant figure looking down over the memories swarming all around. Was he looking on with pride or exasperation? At the end of his 21 years as headmaster of the co-educational independent school (he would leave Culford the year after we all did), surely disappointment loomed large? The 1991 leavers hadn’t quite delivered the grades the school’s marketing had relied upon for recruitment. What had gone wrong?

If Robson was looking down with disappointment, I saw him as someone to blame. As the years had gone on, so any fond memories I left with (there weren’t many) had long since faded. For 30 years I’d believed I was the architect of my own misery at a school that struggled with difference. Their comfort zone was sport. Mine was music practice and that made you a target. Little wonder, as the years went on, I withdrew more and more. And there’s nothing that will secure the attention of the mean-spirited than a self-obsessed anti-social, overly sensitive swot. I made this happen because I allowed it to happen, I had no else to blame but myself.

It didn’t help that my retreat into private practice meant I was the kid with the ‘clarinet stuck up his arse.’ It still stings even reading it back. Music was a refuge – something I could exert control over – but it also resulted in alienation. Comments like ‘he's obviously a queer’ made repeatedly years before I even knew I was gay myself, haunted. A sexual assault and consequent nervous breakdown in the first year sixth either solidified my belief that everything that happened to me was my fault and mine to stop. I left school thinking it was all my fault and that the depression was of my own making. Self-indulgent and self-obsessed, this all could have been avoided if I’d been a little tougher.

In the past couple of years events have shifted my thinking. I have begun to wonder whether the system failed us more than we failed ourselves. Family truths revealed, a near-death experience, and going self-employed have up-ended challenging assumptions, perceptions and a whole host of learned behaviours. What if the nervous breakdown and the depression that followed for three years after wasn’t caused by me failing to engage with the realities of school, but instead the consequence of being in a hostile environment that didn’t serve my needs? What if an absence of targeted care in terms of the ideal support network both at home and at school, exacerbated problems which over time resulted in an event that necessitated an extended period of depression? Looking at both home events and school life certainly made my understanding easier, so too acceptance.

An increasing number of disclosures from peers in the weeks leading up to the reunion revealed surprising experiences. Most stories told a similar story of confusion, vulnerability or isolation, some not only negative but jaw-dropping. Canings, the ruler, the slipper, projectile board rubbers and even a slap in the face from one teacher were the headlines – disappointingly Victorian strategies out of place in the relatively modern mid-80s. Wholly inappropriate advances by a teacher on a school trip, the booting out of an English teacher who struggled to know where the boundaries were, and one man with eye-popping anger management issues, were both shocking revelations and eye-rolling clichés. Undiagnosed ADHD reported on to parents as distraction in class or a lack of focus. Pupils specific learning needs unwittingly stigmatised. Not to mention societal attitudes enshrined in law around sexual identity in the form of Section 28 -- little wonder staff were limited in the scope of their pastoral care, the impact of which would be deep and long-lasting. These disclosures felt validating, painting a bigger turbulent picture that we all weathered and almost certainly were shaped by. We were all part of a system that struggled to support all but the most self-reliant of achievers.

Yet look at that year’s subsequent achievements. Scientists, civil servants, accountants, entrepreneurs, teachers, investors, doctors, nurses, public servants, carers, solicitors, interior designers, musicians and actors. Even a project manager. An impressive array of livelihoods. Noticeable amongst those I spoke to were some undiscovered personalities I wish I’d known before. Dry humour abounded, so too warmth effortless generosity, and openness. In a few special cases, an unfailing ability of some individuals to hold you in their gaze and focus entirely in the moment. Such practised skills are the kind of thing that training companies have built lucrative personal development courses for dysfunctional corporate workplaces. What a shame that the angst of being a teenager had stopped me from seeing that thirty years before.

Just as the brain has a handy way of compartmentalising the good and the bad with a bit of distance and a few good night's sleep, so the opportunity to read over an old school history puts my time at school (1981-1991) in a new, slightly more comfortable context. An opportunity to reframe the past presents itself.

Culford: The First 100 Years was penned by former Head of History F.E. Watson in 1980 to mark the then centenary of the school. The book traces the school’s origins back to 20th May 1881, not housed in the building we’re strolling around during the reunion visit, but in nearby Bury St Edmunds when the school was known as the East Anglian School.

The establishment’s foundations were rooted in Methodist commitments to safeguarding nonconformist beliefs – an institution striving to accommodate difference. One of the school’s homes would be Northgate Street in Bury St Edmunds, later still Northgate Avenue. By 1934, its reputation saw growing numbers of pupils being enrolled, and the need for larger premises anticipated to satisfy increasing numbers. The East Anglian’s subsequent move to Culford Hall the result of a bold and audacious plan proposed by then headmaster Dr Skinner who convinced the board to buy the property from the 8th Earl of Cadogan.

Culford wasn’t (as I perceived it as a kid) a school celebrating a rich history set in acres of parkland, but a nascent business responding to the financial opportunities presented by increased demand. The acquisition of Culford Hall in 1935 from the 8th Earl Cadogan offered a bigger footprint for the East Anglian Boys School and the chance to increase revenue. Agreement for the then £21K purchase (£1.2million in today’s money) was reached in February 1935. Dr Skinner went on annual leave for two months directly afterwards, discovering on his return from foreign climes that pupils would move into the new premises the following September. Even after the move, the school was still referred to as the East Anglian School, eventually dropping EAS in favour of Culford School a few years afterwards. The place I perceived as a teenager was then less than 50 years old, not the establishment steeped in history it projected itself in its grand home.

If the establishment wasn’t as old as its grand location suggested when I joined in ‘81, then its merger with the East Anglian School for Girls 15 or so years before, makes it seem even younger. The merger in the late 1960s met a similar need for growth (or helped overcome financial struggles, depending on how you look at it) for both institutions. A similar pattern of acquisition was followed by infrastructure development, the amalgamation of pupils (my older sister was one) followed by the construction of boarding houses, teaching blocks and associated support services. The school I remember in 1981 was relatively young. Culford was in fact a business in transformation that saw marketing opportunities to exploit in the grand location of the home of former landed gentry.

Reports of that 1960s merger are that schooling was a little chaotic, facilities a little substandard. There was a sense that there had been overreaching ambition combined with a lack of adequate preparation might have resulted in a negative learning experience, something that was surely going to effect the more vulnerable compared to those who were able to focus amid the distractions. Were there more similarities between the experience of my sibling’s cohort with ours? Did one leadership strategy concentrate more on infrastructure than the individual’s needs?

In the final paragraphs of the school's history written in 1980, FE Watson highlights the ongoing strategy for maintaining the Culford business, seeking out of the children of ‘Methodist Ministers, servicemen, parents who were working abroad and some children who had serious home problems. Even at EAS there had been some foreign boys in the school, and in the New Culford the number of foreign children considerably increased ... An unforeseen consequence of the establishment of Comprehensive Schools was the number of parents who, because of their dissatisfaction with the State System decided to send their children to Culford.’ This strategy — capitalising on the aspirational middle classes dissatisfaction with state-driven changes to the education system — undoubtedly continued throughout the 1980s. But just as infrastructure had taken time to meet with demand, had teaching practices and pastoral care struggled to move at pace too?

From this perspective, it's easier to identify change in the ten years I was at school. The new multi-function assembly hall (the location for numerous uncomfortable musical performances) was the pinnacle of headmaster Derek Robson’s achievements, a potent sign of the school’s transformation. Seven years later, a new Biology block put pay to the rotting prefabricated classrooms originally erected in 1978. During that time elderly teachers were replaced by younger ones. Most of my music teachers were only recent graduates. They, like their counterparts in English, history, languages, and mathematics brought considerable energy to their rigorous teaching practice. I’d always appreciated the difference my French and German teacher had made at the time, so too the maths teacher. I just hadn’t appreciated what a pivotal role perhaps they were playing in the school’s ongoing transformation at that point in time. The Culford I left in 1991 was, twenty years after its establishment as one of the first co-educational schools, was in 1981 a relatively new entity. Me and my peers received our education at a turbulent time. And we still came good. Quite whether that is to the credit of the school itself, I’m not entirely sure.

The school feels vast in comparison to what it was then. The central teaching block has been modernised, the sports provision expanded to make for a dizzying experience. Art features heavily and prominently, there’s a dedicated drama space, and a grand library with considerably more resources than we had in our day. Some things have stayed the same. The cooking time for lasagne, the range of salads, the trays, and the table that lunches are eaten from offer an unsettling sense of continuity.

It is a shame that my mother, now subject to the meanness of dementia, will never know the bigger picture. She’ll never know the reality of what she was fighting admidst our own family crisis. She’ll also never know the transformation our reunion has had. The true value of learned behaviours stemming from an anxious attachment style shaped by my dual environments of home and school are now significantly diminished. Friendships formed in response to the legacy of Culford are now under an inevitable spotlight. With old trauma reframed, so a new liberated path can be pursued. By examining the past, so the present can be reframed. It just takes a daunting reunion and some recovery time.

One week on and a slew of photographs to pore over, a surprising development: our class is a family shaped by an environment that was at the time we all met in the midst of significant change. The school as a business had embarked on a period of growth and was only just keeping up with demands. A generational shift in styles of teaching and the development of pastoral care was, arguably, yet to come. Was our year of relative misfits pivotal? I like to think so, though some may feel this is overstated.

Yet the recall is strong, the faces still instantly recognisable. The intervening years have cleared the angst and the clutter allowing the warmth to emanate. Photographs raise an instinctive smile — memories of unexpected moments on a demanding day, making this seemingly unlikely bunch an unexpected family. Like a lot of families, especially mine over the past few years, new information comes to light later in life that provides new context for what was going on in the past.

These insights are precious, potentially setting us on a different slightly prettier path. There is already talk of another bigger reunion for a years time, hotels and hottubs, dance tents and en-suites. In the meantime, diaries are getting flicked through, tentative arrangements getting penned in. A mighty achievement in itself. Shame there’s not an internationally recognisable grade for it.