Everyone needs a Sid

What Britten’s Albert Herring teaches us about personality, rebellion, and growing up

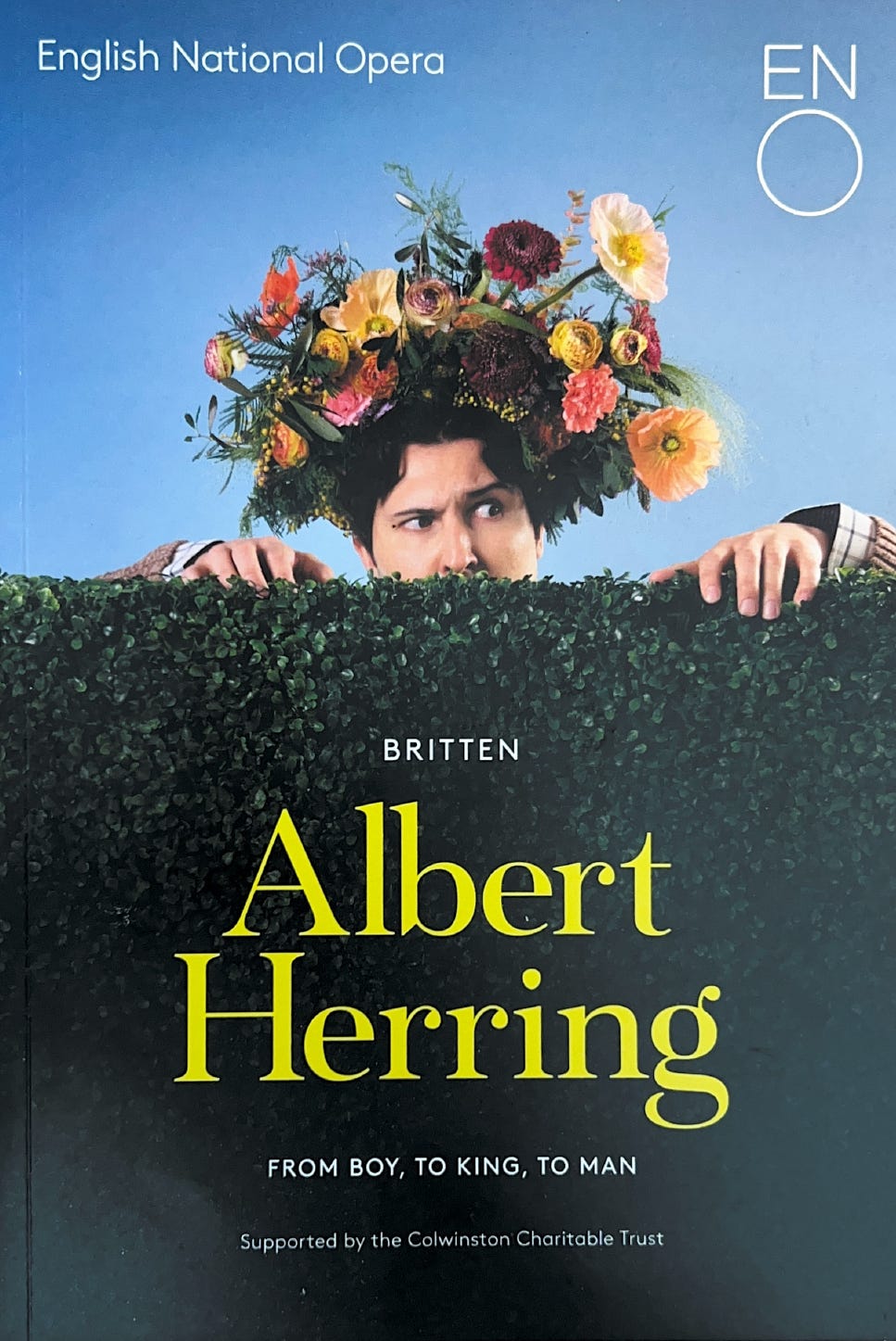

English National Opera’s latest disappointingly and inexplicably short run of Benjamin Britten’s Albert Herring in London and Salford was a timely production with unusually good marketing to boot.

Greengrocer’s son Albert Herring ends up being anointed King of the May when no other suitable candidates for Queen of the May can be agreed upon by the town council. Herring’s ascension to the throne isn’t the rite of passage the town matriarch Lady Billows resolutely regards it.

Instead, Albert’s real ascent into manhood comes as a result of his friend Sid, the butcher next door, surreptitiously lacing Albert’s lemonade at the party, after which the King of the May goes on a bit of a bender. Disruption does more to educate Albert than preserving tradition. Like the posters and the programme clearly state, this is a story of Albert from boy, to king, to man. Tidy.

Look for the themes in a work and there’s usually a parallel somewhere close by that slides in comfortably alongside. It doesn’t necessarily have to be a universally accepted one either. Commenting on the first half to my host as we headed for an interval drink, I was convinced the council’s difficulty in finding the right candidate and settling on a fudge was a metaphor for the present malaise society finds itself in. The absence of the ‘right’ leader simply highlights how the expectations that shore up tradition are outdated, restrictive, and no longer fit for purpose. The only way to respond to that is to subvert that generation’s obsession with preserving tradition. Sid, though not the lead in Britten’s ensemble cast, plays a key role in turning everything on its head. Everyone needs a Sid in their life.

We spend a lot of time focusing on explaining the art in the belief that this will aid comprehension. But this keeps us at a transactional level, leaving us wading around in the detail. Identifying themes from a few steps back provides a perspective that makes for a more inclusive experience. It’s often easier to relate to themes than it is to the details. Leave the detail until it’s absolutely needed.

This shift in thinking has been reinforced by a recent training course on Hogan personality assessments. Hogan’s psychometric tool identifies predicted behaviours based on the answers respondents give to 150 rapid-fire questions. These thirty-six predicted behaviours are rooted in identifiable values, positive actions, and likely derailers. Each of these thirty-six scales has a series of subscales that drill down into more detail. The two-page bar graph is a little overwhelming at first sight — two pages of colour-coded judgment that inevitably triggers a range of emotions including some of the finest like denial, rage, hurt, and shame. What you experience in response is of course documented clearly in the very profile you’re looking at. But the key to Hogan is, more than MBTI, DISC, Clifton or some of the others, its granularity. It’s not a verdict so much as a data source. It is like being finally handed the operating manual you wish your parents had access to before they left the hospital. Knowing one’s likely positive and negative behaviours in response to certain situations isn’t a sentence, it’s a path to freedom. Though, of course, this outlook depends on what’s found in your Hogan profile.

The effect is profound. By looking for themes, it’s possible to maintain a distance from the subject. This allows for frictionless thinking that can spark imagination and develop all manner of different strategies. These don’t necessarily need to be realistic or actionable. Rather, they’re more excursions on which ideas can develop and maybe even flourish. Exploring ideas thematically affords the opportunity to adopt alternative approaches or perspectives far more easily than tackling the challenge transactionally. Thematic analysis yields far more creative opportunities.

But there’s a cost too. Or a threat. One of the two. This preference for imagined alternatives, combined with appetite-fuelled, fast-paced thinking, means others are often left behind. The gap inevitably triggers a defensive response. The resulting chasm often feels difficult to bridge. Impatience and frustration occupy the space. Impetus is lost. A cost-benefit analysis informs shifting down a gear or two when the need arises. Notebooks suddenly become ever more important, writing a haven where third-horizon thinking is given space to breathe.

This pattern-based approach is what composers do, not least in sonata form found in symphonies and concertos, where the theme (the initial musical idea) is taken on a development path. Risk and transformation are found in this form, not an act of communicating certainty but exploring possibility. The latter feels far more enticing and potentially rewarding.

What might Herring’s Hogan profile look like? To use Hogan language for a moment, Albert is a classic high-Dutiful, high-Prudent, low-Ambition profile: dependable, deferential, and risk-averse — the archetypal executor. Before his coronation, he’s the reliable team player everyone trusts to keep the shop open and the rules intact, demonstrated by his ‘bright-side’ strengths — conscientiousness, honesty, predictability. These strengths win him community approval, but also trap him in compliance. Under pressure, those same traits tip him into his ‘dark side’ derailers. His tendency to over-accommodate, be cautious, and lack assertion are turned upside down.

Librettist Eric Crozier’s story doesn’t rewrite Albert’s profile; it simply develops the tools Albert has to express it fully, effectively giving him permission to act authentically. When Sid spikes his lemonade, Albert’s repressed Mischievous and Bold tendencies surge. He experiments with risk, autonomy, and pleasure. By the end he hasn’t become a different personality type — he’s still the executor — but now a self-directed one. He is more confident, comparatively more at ease testing limits and making mistakes. He has grown.

In exploring a long-loved Britten opera like Herring in this way — thematically rather than via critique of performance — the work rewards with deeper thought. It is no longer a performance I’ve battled late-running trains and a poorly planned walk from the station to get to. Instead, pattern matching makes a good story linger and the craft involved to bring it to life something one can return to again and again. This makes the subject live longer and resonate more, elevating the story beyond a poke at the parochial politics of an East Suffolk town. It’s a metaphor for challenging convention, risk-taking, and confidence-building.